Linocut printing is a relief print process that involves cutting into a sheet of lino, applying ink to the uncut shapes and lines, and then printing on to a flat surface, usually paper. Lino is an abbrieviation of linoleum, the material associated with kitchen floors, which was originally made of cork and pigment mixed with oxidised linseed oil, and backed with a loose weave hessian. Nowadays, alternatives to the traditional battleship grey lino include a variety of substrates made of PVC including Softcut, Speedy Carve and Japanese vinyl. Below is a summary of the main differences, along with some tips on how to get the most from your linocut printing session.

![]()

As mentioned in Colin Blanchard’s article on his recommended tools for linocut printing, you can divide the different cuts you will want to employ in your lino printing into three main groups: fine lines, dashes/textures and clearing. Five Pfeil tools are a lifelong investment for relief print (both wood and lino) with regular sharpening. However there are other good relief cutting tools available, including those by Flexcut, Jackson’s woodcut tools (which can also be used for lino) and RGM.

Cutting fine straight and wavy lines, clearing a broad area and cutting to the edge of the block demonstrates the differences in character of each of the blocks, the results of these tests are below. Following this you’ll find my tips on the best ways to draw your design on to your block. Finally you’ll see how these blocks fair when inked up and printed, using Caligo water based ink and Strathmore Printmaking paper.

First Impressions

The grey lino is the stiffest, hardest block out of the four. It has a very slightly dimpled surface and a hessian backing. On occasion, battleship grey lino will have a slight curve, caused by the lino being stored on a roll. This can make a very even print more difficult – especially when using a press – so if you are after a very uniform layer of colour in your print I suggest gluing your lino to an MDF or plywood board – making sure that you apply substantial weight to your block as the glue dries, to stop the lino bouncing back to its curved state.

Softcut is creamy-beige in colour, and has a smooth glossy surface, with a matt texture on the reverse. It is very flexible, but not spongey – it does not easily compress if you apply pressure to its surface.

Speedy Carve is pink, and even bendier than Softcut, in fact it would be ideal for printing on a curved surface. It has a slightly spongy feel when you press into it. It is a popular material for stamping, rather than relief print – and so is made with printing by hand in mind. It is double sided.

Japanese vinyl is perhaps the most stylish-looking of the relief print blocks, with a green side, a blue side and black core. You can carve both sides, and the black core makes it easy to see where you have cut. It is more rigid than Softcut but has a degree of bendiness.

![]()

Clockwise from top left: Traditional grey lino, Speedy Carve, Japanese Vinyl and Softcut.

Which Lino Block Is the Most Eco-friendly?

As linocut tends to accumulate a lot of offcuts destined for the bin, I feel it important to point out that battleship grey lino is the only fully biodegradable of the relief print blocks, and will not release harmful gases or toxins as it breaks down. The other blocks are made from PVC and can be recycled, although to find a means of recycling your relief print offcuts may prove difficult. However, PVC production requires relatively low energy in comparison to other plastics, and because it is relatively resistant to breaking down, only releases small quantities of dioxins. It is one of the more eco-friendly plastics, but using wood from a sustainable source or genuine lino will always be more eco-friendly.

Cutting Fine Lines

Fine lines are often the first cuts to be made when carving a relief print. It’s a good idea to use a fine line to outline shapes before clearing the remaining lino, as it can help prevent slips and unintended cuts. Fine lines can also be employed for hatching and cross hatching effects as well as textures, such as fur or hair.

A good technique for making a controlled line is to rest the index finger of the hand you are holding your tool with, on the top of the blade, but then use the index finger of your non-cutting hand to help steer the blade in the direction you are going. This should help to even the pressure out across both hands. And of course, never cut towards yourself or your non-cutting hand – by turning the block you can ensure your blade is always pointing away from you.

Needless to say, the harder the block is the harder it is to cut, but that’s doesn’t mean that a softer block is superior, as it can be easy to slip and cut where you didn’t intend. It can also be harder to control the depth and width of a line. If you find your grey lino too hard to cut into, a top tip is to warm it first as this helps to soften it. Either sit on your lino while you have a cup of tea, or iron it on a low temperature, or put it on a radiator for 5-10 minutes. If it gets almost too hot to handle, it will be more likely to crumble as you cut it (especially if your cuts are too deep) so exercise caution!

![]()

As grey lino is the hardest of the blocks, good technique can help a lot in achieving even cuts without putting too much pressure on your fingers. If you can, practice on a separate offcut before you embark on your work so that you can familiarise yourself with how hard your block is and practice your cutting technique. For a fine line, you only need to make a 1 – 1.5mm deep cut in order for the line to register on your print, and there is no benefit in cutting any deeper, which would make the cutting more difficult.

![]()

Cutting wavy lines are generally trickier. You need to go fairly slowly and turn the block when you can, in order to achieve a flowing wave (I hasten to add, cutting waves in lino is much easier than cutting into wood!). The hardness of the grey lino helps to keep the cuts even and flowing.

![]()

Softcut by comparison to grey lino is easier to cut in general, but the block certainly feels more elastic. With grey lino there is a satisfying ability to flick and break the end of a carved line, but the elasticity of Softcut demands that you scoop your cutting tool upwards to end the line, which can be easy to forget if you are unused to Softcut. If you reach the end of your line and the cut has not broken away from the block, you could try pulling it off with your fingers, but this may tear the block slightly and cause the cut to go on for longer than you wanted. Wavy lines are a little more unpredicatable, the edges of the lines are at times a little rough and jagged. A greater familiarity with this block will no doubt help!

![]()

Speedy Carve is even softer than Softcut and the tool glides through the block. Its softness means you need to practice to ensure an even thin width and depth. Because of the need to raise the tool up in a scoopy action to end a cut line, the lines tend to appear to have tapered ends, although this can be minimised with practice.

![]()

The Speedy Carve can be a little difficult to control when cutting wavy lines – with the softness of the block making it easy to slip as you are cutting and therefore undermine a controlled, flowing line. Such issues will disappear with practice.

![]()

Japanese vinyl is softer than grey lino but harder than Softcut or Speedy Carve. The black core is very useful in being able to see where you have cut clearly. Cutting wavy lines is relatively easy in comparison to the softer blocks.

Clearing

Clearing refers to removing a whole area to leave an unprinted shape in your linocut. I have found the quickest way to clear large areas is to use a large U shaped tool to cut out parallel lines across the area you wish to clear, and then employ a flattter and broader U shaped tool to cut inbetween the original cuts. This is easier than cutting into an entirely uncut expanse of lino.

![]()

The key with grey lino is to go slowly to avoid slipping, and use both hands where you can for maximum control. The cuts will then have clean edges. If you are clearing a large area, its common for chatter to creep in at the printing stage – this is when ink reaches the inevitable ridges found within a cut area. This is the greatest bugbear of many linocut printmakers! You could consider incorporating chatter into your work and deliberately clear in a certain direction so that the chatter marks complement more intended marks. Or, if you don’t like the sound of this, you can wipe ink away with a rag (I would use a clean dry rag and avoid water or solvent as this can result in smears or grease marks in your print).

![]()

Another solution is to make a paper mask to cover your cleared areas – very thin paper such as newsprint is ideal as it is less likely to get in the way of the printing process. In my experience, there is no point in trying to smooth out all the ridges in the cleared area as no sooner as you have cleared one ridge you will inevitably create two more!

![]()

Cutting right to the edge is easy and satisfying with grey lino, the cuts are clean and the lino breaks away easily. By comparison, Softcut is easier to clear with, a Pfeil tool glides through the block with ease. When cutting to the edge of the block, the plastic has a tendency to fold over itself, and as a result my attempts to cut right to the edge are scuppered, leaving a little uncut border on the edge (illustrated below). This is easily rectified by cutting back from the edge inwards, but adds time to the process and is a little more fiddly. Clearing and cutting to the edges on a block of Speedy Carve was a similar experience. With a thickness of 0.6mm, it is twice as thick as the other blocks, and this combined with its softness means it’s possible to inadvertently make unecessarily deep cuts. To avoid this it’s really important to use both of your hands to steer the cutting, and also to ensure you have your block on a completely flat surface.

![]()

Clearing an area in Japanese vinyl was a similar experience to Softcut as well. If you want to minimise the amount of scooping (and possible tapering of a cut) that you need to employ in order to make a clean cut, you could use a scalpel to create clean edges at the end of your cuts. This would then allow you to keep your cuts at a similar depth for the whole length of a cut, and minimise chatter. Although the edge of a block does fold over itself to a degree when cutting to the edge of Japanese vinyl, it doesn’t stop you from making a cut right to the very edge, so in this sense the Japanese vinyl is more like the traditional lino than the Softcut or Speedy Carve.

![]()

Transferring Images on to Lino

A popular way to transfer a design on to lino prior to cutting is to use carbon paper. By placing your design on to your block with a sheet of carbon paper face down in between, you can then use a sharp point such as a pencil to go over the lines of your drawing, and the pressure will transfer carbon on to your block. Carbon paper is not recommended for use on Softcut or Speedy Carve. These blocks are too soft and rubbery, and too much of the carbon transfers on to them. The process becomes very inaccurate and if making a multi-block print, could cause real problems when registering separate layers at the printing stage. Instead, I recommend drawing your design on tracing paper using a soft pencil, then placing the drawing face down on your Softcut or Speedy Carve and going over the back of your lines with a sharp, hard H or 2H pencil. This is a much more accurate way to transfer an image (you can also do this on traditional lino). This technique will also ensure your design is transferred back to front, which is what is needed for the printed image to appear the right way around!

Indian ink pens and Sharpie pens are also great for drawing designs on all these blocks, although be aware that sometimes these marks will transfer on to your paper when printing. If this happens at the proofing stage try wiping the block with a little rubbing alcohol or methylated spirits on a rag to remove the marks, then allow to dry before you ink up again.

White pencil is a smudge proof medium for drawing on to relief print blocks and works best on grey and Speedy Carve. It is not recommended for Japanese vinyl or Softcut as it is very faint and rubs away easily on these surfaces.

Printing the Blocks

I tried printing with each block twice – once by hand using a baren and then using an Albion printing press. A baren is a disc traditionally made from a coil of string wrapped in a bamboo leaf. It is designed for use in Mokuhanga printmaking but is a popular tool for burnshing all relief prints made by hand. An Albion press is a vertical pressure iron hand relief printing press that was invented by Richard Whittaker Cope in 1820, and is known for its ability to produce a high degree of uniform pressure.

The Difference Between Printing by Hand and Printing with a Press

Printing by hand is no better or worse than printing using a press – it’s just different. When printing by hand you can control how much pressure you apply, increasing or decreasing the saturation of colour applied as you wish. Hand pressure will be much less than the pressure you can achieve with a press, and so you’re more likely to achieve a textured layer of colour (although you can also achieve this with a press too!). You can apply pressure using a baren or a spoon (wooden or metal), and thinner papers will be easier to work with, as you won’t need as much pressure. Printing by hand is more time consuming, but also allows you more control.

By contrast, using a press will produce an even pressure across your print, quickly. This is particularly desirable when producing an edition of prints, and the same amount of pressure is needed across the image. You can use papers of any thickness, although thicker printmaking papers (such as Stonehenge or Fabriano Rosaspina) will also allow you to introduce an embossed quality to your work if desired.

Lino

![]()

Lino, Hand printed

Here you can see the tiny dots of white in the printing, where the ink has not applied. This is partly because of the amount of pressure I applied and also partly because of the slight texture on the surface of the lino (which can be sanded away). Some of my finest lines were flooded with ink, which indicates I need slightly deeper cuts. Here’s what happened when I printed using the press:

![]()

Lino, Press printed

Here you can still see the texture of the lino, but the white dots have now gone, thanks to the higher degree of pressure. This has also pushed some ink into the other marks, including the wavy lines and the cuts to the edge of the block. The area I cleared has less crisp edges than the hand printed block, but this can be remedied by reducing the amount of pressure.

Softcut

![]()

Softcut, Hand printed

The Softcut prints beautifully by hand, because the surface is smooth the amount of texture you can get is wholly dependent on the pressure you apply. The marks have a clean cut quality.

![]()

Softcut, Press printed

When printing with a press, the marks flooded a little, but again this can be controlled by reducing pressure. Other than that the Softcut withstood the vertical pressure of the press very well. I have used Softcut in an etching press and it was prone to slipping and the cuts closing in under pressure, but these issues did not occur during this test.

Speedy Carve

![]()

Speedy Carve, Hand printed

The printing results of Speedy Carve were very similar to Softcut when printed by hand, although you don’t need as much pressure. It’s clear why this is such as popular material for stamping. It prints beautifully with lovely clean cut edges.

![]()

Speedy Carve, Press printed

By contrast, I would not recommend Speedy Carve for use in a press. It’s too soft and spongey, and as a result cuts do not appear crisp. The evenness of the print was great, but if I were to reduce the pressure to try and achieve cleaner cuts, this evenness would not be guaranteed. The smudgey edges of the overall rectangle show how the block has squashed in the press during the printing.

Japanese Vinyl

![]()

Japanese Vinyl, Hand printed

Another completely smooth surface, Japanese vinyl is a great surface for hand printing with, you can achieve an even colour with not too much pressure, and the cuts appear with clean edges.

![]()

Japanese Vinyl, Press printed

Japanese vinyl is very well suited to printing with a press as well, with clean looking cuts, and a good impression of a layer of colour.

Summary

If you intend to print using a press and edition a number of prints, traditional lino or Japanese vinyl are both great choices. Softcut works as well, but is better for smaller sizes of work. All of these blocks are suited to hand printing, although you may need to lightly sand your grey lino if you wish to have a relatively even print texture. The ease of cutting Speedy Carve makes it ideal for making irregular shaped prints or stamps.

Related articles:

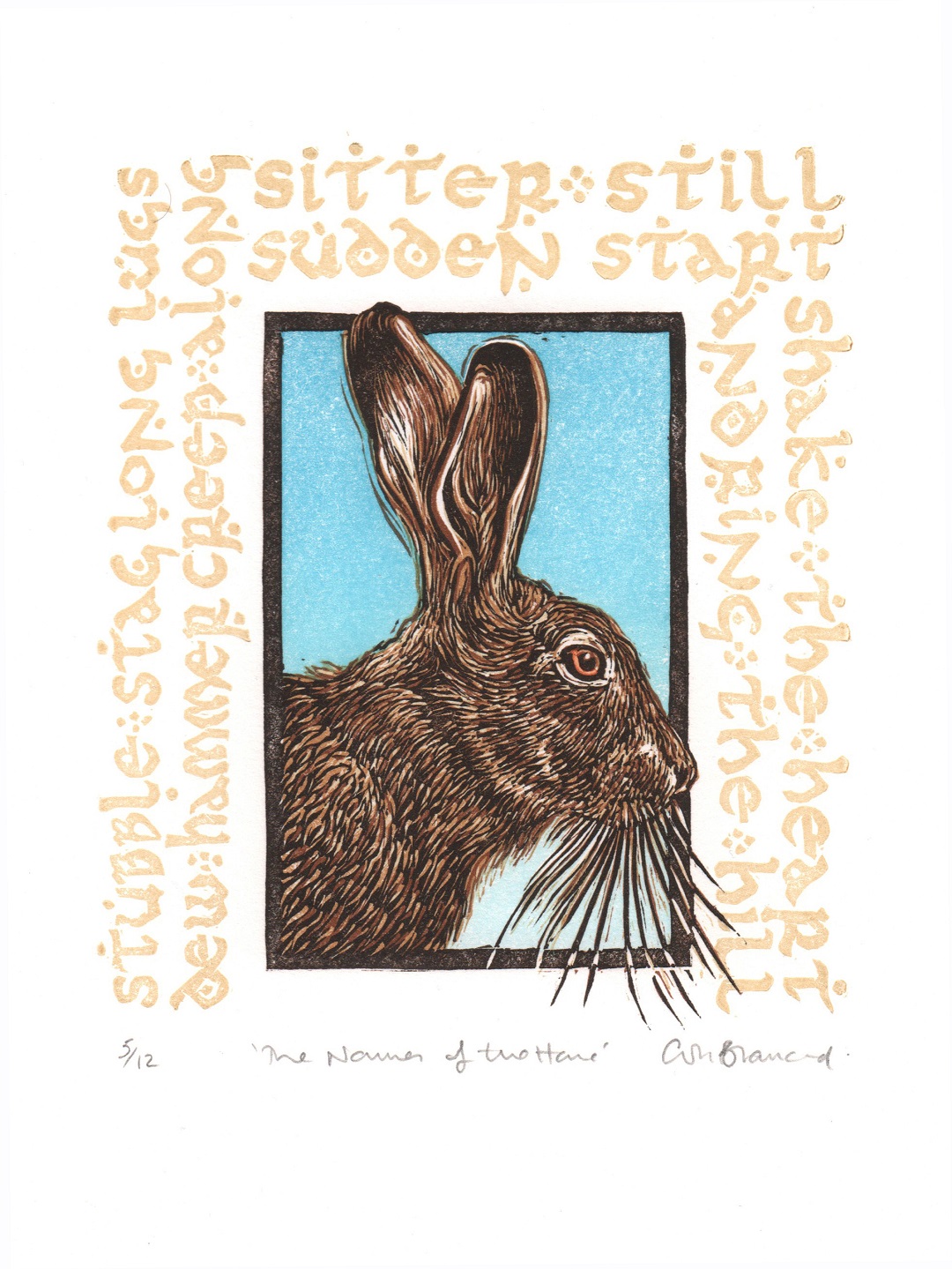

5 Recommended Pfeil Tools for Linocut by Colin Blanchard

Sharpening Linocut Tools by Colin Blanchard

Rachael Louise Hibbs: Botanical Inspired Linocut Prints

Relief Printing with the FOME Etching Press

Relief Printing at Jacksonsart.com

The post Printmaking: Comparing Lino, Softcut, Speedy Carve and Japanese Vinyl appeared first on Jackson's Art Blog.